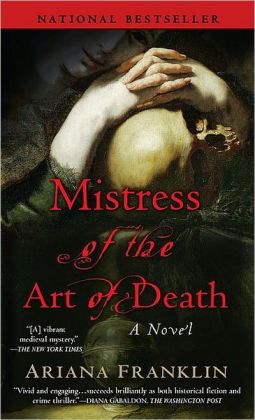

I suppose reading mysteries is fairly benign, but I harbor a certain shame that they aren't somehow as worthy as other reading, that is, until I know someone else is also a mystery fan, I'll talk first about the more erudite things I've read. With the occasional exceptions of really quality writers who create fine complex characters or take on weighty social issues or teach me more about a culture (P.D.James, S.Paretsky and Tony Hillerman come to mind as examples), I tend to think of them as my escapist literature--my "comfort food" reading. So recently, having had my fill of reviewing YA books, I immersed myself in a couple of mysteries, Dead Canaries Don't Sing by Cynthia Baxter and Mistress of the Art of Death by Ariana Franklin. For anyone who likes animal characters to spice up their mystery soup, Dead Canaries is good fun; the protagonist is a veterinarian and amateur sleuth who is usually escorted by her two rescued dogs, a tail-less Westie and a one-eyed, 3-legged dalmation. She also has Cat (short for Catherine the Great) and a parrot who holds a key clue in this tale. Another animal-centric series I really enjoy is that by Rita Mae Brown; these are told from the point of view of the protagonist's cats and a dog--who claim to solve the mysteries long before their sensory-challenged humans do. But the greater of the two mysteries I read, the one that really grabbed me--you know the like, can't put it down, stay up too late, everything else goes by the wayside until I'm finished--was Franklin's Mistress. I profess a certain fondness for medieval mysteries (e.g., Umberto Eco, Sharon Penman, Candace Robb, Barry Unsworth) and this one features a woman who is a pre-cursor of the forensic specialist, trained at the medical school in Salerno, and recruited to go to Cambridge to help solve the murders of several children. Not for the faint of heart since it's fairly explicit about how the children are murdered, but rich with period details, the politics and tension between the Church and Henry II, the social strictures under which women, Jews and other non-dominant groups had to maneuver. Several characters in addition to the protagonist are well-developed and an author's note on the factual basis of several aspects of the story added to my appreciation of this well-paced story. I really hope there will be a sequel...

Keeping track of what I read by jotting down my reactions, providing information about the author, and linking to additional reviews. And occasional notes on other book related things...

Monday, September 24, 2007

As vices go...

I suppose reading mysteries is fairly benign, but I harbor a certain shame that they aren't somehow as worthy as other reading, that is, until I know someone else is also a mystery fan, I'll talk first about the more erudite things I've read. With the occasional exceptions of really quality writers who create fine complex characters or take on weighty social issues or teach me more about a culture (P.D.James, S.Paretsky and Tony Hillerman come to mind as examples), I tend to think of them as my escapist literature--my "comfort food" reading. So recently, having had my fill of reviewing YA books, I immersed myself in a couple of mysteries, Dead Canaries Don't Sing by Cynthia Baxter and Mistress of the Art of Death by Ariana Franklin. For anyone who likes animal characters to spice up their mystery soup, Dead Canaries is good fun; the protagonist is a veterinarian and amateur sleuth who is usually escorted by her two rescued dogs, a tail-less Westie and a one-eyed, 3-legged dalmation. She also has Cat (short for Catherine the Great) and a parrot who holds a key clue in this tale. Another animal-centric series I really enjoy is that by Rita Mae Brown; these are told from the point of view of the protagonist's cats and a dog--who claim to solve the mysteries long before their sensory-challenged humans do. But the greater of the two mysteries I read, the one that really grabbed me--you know the like, can't put it down, stay up too late, everything else goes by the wayside until I'm finished--was Franklin's Mistress. I profess a certain fondness for medieval mysteries (e.g., Umberto Eco, Sharon Penman, Candace Robb, Barry Unsworth) and this one features a woman who is a pre-cursor of the forensic specialist, trained at the medical school in Salerno, and recruited to go to Cambridge to help solve the murders of several children. Not for the faint of heart since it's fairly explicit about how the children are murdered, but rich with period details, the politics and tension between the Church and Henry II, the social strictures under which women, Jews and other non-dominant groups had to maneuver. Several characters in addition to the protagonist are well-developed and an author's note on the factual basis of several aspects of the story added to my appreciation of this well-paced story. I really hope there will be a sequel...

Friday, September 7, 2007

Dingley Falls Fails, and Other Books I Did Like

Ah well, just goes to show that no two readers read the same book...where did I just read something about 'the reader writing the book'--oh well, another senior moment. Anyway, I was trying to work my way through Nancy Perl's recent recommended reading (see previous post on The Grand Complication) by tackling Dingley Falls, which, from NP's account sounded irresistible. While she was charmed by the extensive cast of characters, I was overwhelmed, and after reading over 120 pages, still didn't care very much about any of them. One of Nancy Perl's rules is the 'Rule of 50', i.e., there are too many books and not enough time, so 50 pages (minus 1 page for every year your chronological age exceeds 50) is sufficient to make a decision about a book. Obviously I still haven't embraced this wholeheartedly, but I'm working on it. I will agree with her that the novel reads like an elaborate soap opera, but I was never a big fan of soaps, so maybe that's the problem.

But other books have come to mind because of recent conversations with my book buddy Sara--books I really did like. Once when our talk turned to France I was reminded of a really wonderful little memoir by another Sarah (with an 'h") called Almost French: Love and a New Life in Paris. Australian journalist Sarah Turnbull moves to France to live with her true love and for all her infatuation with Paris and the French, she is never really accepted by them but always considered an outsider. On the other hand there are some things she's willing to change-- and some she is not--in order to fit in. It's not just that she's Australian, it's that they are so French. Well, anyway, it's a somewhat humorous and not unkind inside look at culture shock and one woman's eventual success at coping.

Then Sara sent me this very evocative little poem ("Books" by Dorianne Laux) about someone graduating from high school and standing on the brink of whatever is to come after that and, incidentally, the person has stolen a book from the school library. Which reminded me of a really wonderful book, ostensibly written for young adults (but I can't imagine a not-young adult NOT liking it for that reason) called The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. In contrast with Dingley Falls, this was a book where I came to care deeply about all the characters. The young protagonist, Liesl, is farmed out to a foster family near Munich as the Nazis are on the rise and the Hitler Youth are snapping up any youngster of school age. Her mother has fled after burying her son, Liesl's younger brother, and Liesl steals her first book, a gravedigger's handbook. It is this book that her foster father uses to help her learn to read. Along the way, an old debt is repaid by taking in and hiding a Jew in the basement of her foster parents' home and he and Liesl become fast friends. What makes this book really interesting is that a fairly benevolent Death is the narrator. He is kept awfully busy by the events of the war, but not too busy to check up on Liesl from time to time. What also makes it poignant is the significant and layered role that books play in her life. For example, she steals her 2nd book from a pile set on fire during a Nazi inspired book burning, and Liesl reads from her small hoard of stolen books to the gathered neighbors in the air raid shelter to take their mind off what is happening above. I really liked this book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)